Chances are, if you’re reading this, you, or someone you know is experiencing a disturbance in mood. This will look different for different people: anything from outwardly expressed sadness to a sense of malaise, a general lack of zest or interest in life.

We’re glad you’re here.

Whatever you’re going through, it’s great that you’re seeking more information. It can be very disorientating when your mind and emotions feel beyond your control. Whether a diagnosis of depression is the right fit for your experience, or some other explanation, you can be assured that you are not alone and that there are reasons for hope.

This article will map out possible causes for a depressed mood, explain what is meant by the term ‘clinical depression’ and how it can be treated, offer some reflections on how depression fits into a biblical worldview, and suggest ways to get help.

[1] I am indebted to Rev Keith Condie for this framework

Do I—or does someone I know—have depression?

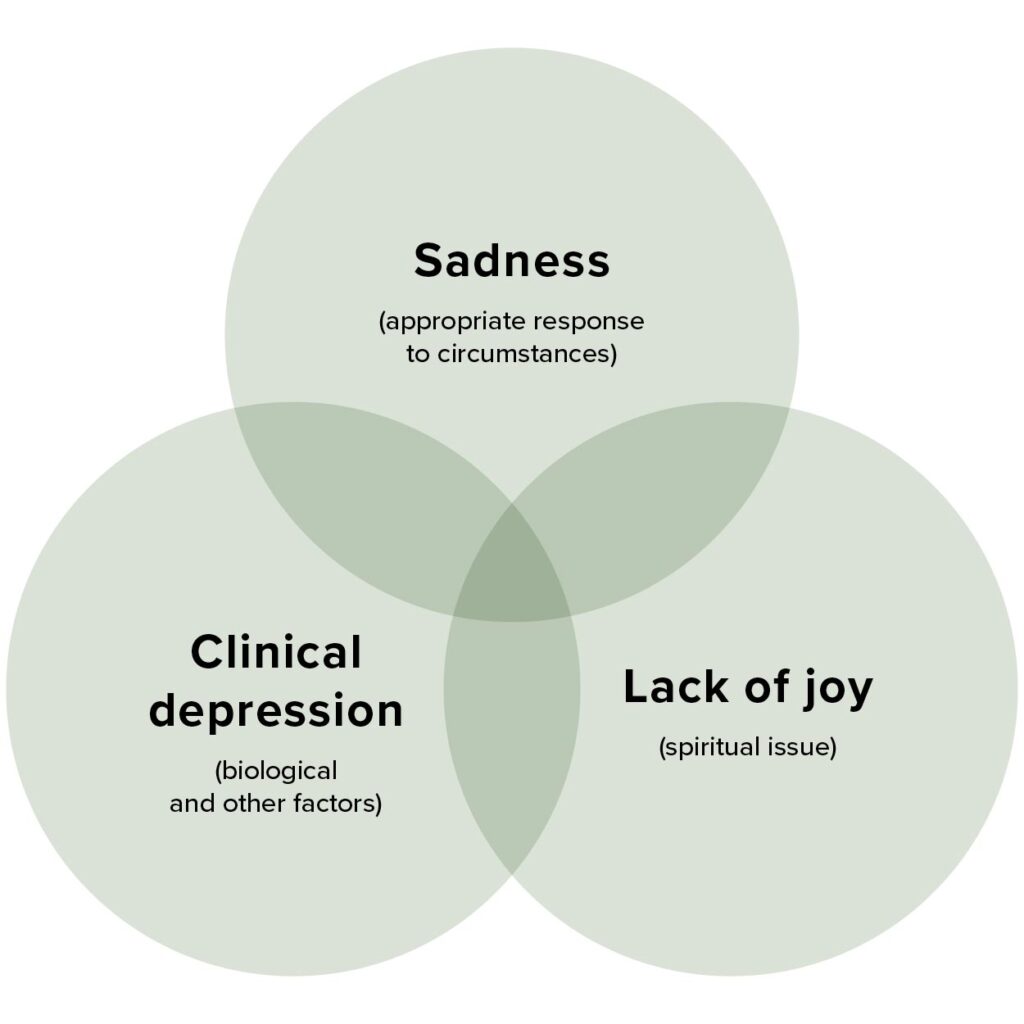

To answer this question, let’s begin with a broad lens. This is because it is normal to experience shifts and downturns in your mood or general outlook in life. Consider the following diagram which offers three possible overarching explanations for a disturbance in mood.[1]

Sadness is a normal and appropriate human response to experiences of loss. Grieving the death of a loved one is an obvious example, which can potentially cause a prolonged period of intense sadness. Other losses in life, often inherent to changes such as moving house, finishing a role, or coming to the end of your holiday, might also trigger sadness. Sadness is also appropriate when we are hurt by others. Interestingly, as a vulnerable emotion, sadness is sometimes masked by a stronger emotion like anger, or by an emotional numbness, and can be hard to correctly identify even within ourselves. To be sad is not necessarily to be clinically depressed, however, it is absolutely a valid reason to talk to a caring friend or other helper. Buckling down and riding it out is generally not the most adaptive way to cope with negative emotions. Emotions signal what matters to us. Talking with someone who knows us and can listen well helps to make meaning from difficult emotions and circumstances.

An underlying lack of joy might be another cause for a downturn in mood. This explanation is a spiritual one, stemming from feeling disconnected from God. Some reasons a person might find themselves without joy include ministry burnout, a besetting sin, spiritual trauma involving a Christian leader, or an inability to maintain rhythms where we draw near to God such as regular prayer and meeting with his people. Again, if this resonates with you, please talk to someone. In this case, a pastor or Christian mentor would be a great candidate for listening and bringing insight. It is also helpful to remember that God is a patient Father, eager for you to know how much he is for you, even when you feel far off and joyless.

Before we move to clinical depression, notice that helpfully, the Venn diagram overlaps these explanations. A change in mood could fit somewhere in an overlapping piece. For example, it is possible that grief from a relationship breakup can trigger some biological and psychological processes that meet the definition for clinical depression. Or that clinical depression results in feeling faraway from God (this is often reported by Christians going through depression). This diagram represents some theories for explaining what you are observing in your (or your friend’s) behaviour with the end goal of finding the right help that will make a difference. We want to avoid using a hammer when we need a wrench! To that end, inviting ‘experts’ into the picture can help narrow in on the best explanation and best way to respond.

The term ‘clinical depression’ refers to a medical diagnosis of depression, of which there are a few types. In this case, ‘experts’ who can identify if you have depression might include a GP (a great place to start, especially if they have a reputation of being good with mental health), a psychologist, psychiatrist, psychotherapist (or therapist for short), counsellor, and a social worker trained in mental health. Information you access online (such as this article) is a great resource but cannot replace the training and experience of a mental health professional.

The main type of depression is known as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). To be diagnosed with MDD, there are nine key symptoms to be looking for, and a person must have at least five of the symptoms present which include at least one of the italicised symptoms, for at least two continuous weeks. The symptoms are:

- Feeling sad, depressed or numb for most of the day

- Reduced ability to find enjoyment in day-to-day activities

- Change in eating pattern, such as a loss of appetite or significant weight gain

- Change in sleep pattern, either more or less sleep

- Change in bodily movement, either noticeably agitated or slowed down

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feeling worthless or inappropriately guilty

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- Repeated thoughts of death and suicide

Other types of depressive disorders are distinguished from MDD by:

Intensity of symptoms, such as Melancholia, a more severe version of MDD, marked by a loss of pleasure in almost everything

Additional symptoms, such as the presence of psychosis in Psychotic Depression

A different timeframe, such as Persistent Depressive Disorder (also known as Dysthymia) which is present for two years or more

Particular causes, such as Perinatal Depression (occurs during or after pregnancy), Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (symptoms of depression comparable to MDD in intensity but not meeting the two-week timeframe because they come and go according to a woman’s menstrual cycle), and Seasonal Affective Disorder (affected by light exposure, emerging in winter months)

If you’re wondering if depression might be the best explanation for your mood disturbance, this depression test may help bring some clarity. Of course, talking with an expert in mental health will bring greatest clarity and hopefully a path toward treatment.

Why do Christians get depressed?

The short answer is because Christians are human beings living in a broken world. Let’s unpack this.

Christians are human beings

The bible has a lot to say about what it means to be a human. Humans are:

- Physical / “For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb.” (Ps 139:13, NIV)

- Social / “The LORD God said, ‘It is not good for the man to be alone. I will make a helper suitable for him.” (Gen 2:18)

- Cognitive / “Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy—think about such things.” (Phil 4:8)

- Emotional / “There is a time for everything… a time to weep and a time to laugh, a time to mourn and a time to dance” (Ecc 3:1a, 4)

- Spiritual / “From one man he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth… God did this so that they would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from any one of us.” (Acts 17:26a, 27)

Incredibly, each of these dimensions are woven together in a balanced unity. Where other worldviews might favour one dimension over another, such as pitting bodily concerns over our spiritual identity, the bible holds that every part of us must work together in worship of the Creator. For the believer, the Holy Spirit is working in us to bring our bodies, relationships, thoughts, emotions, and heart-desires in conformity with the Lord Jesus. Of course, our need for the Spirit to be doing this work leads us to our second idea.

Christians live in a broken world

We, in our flesh-and-soul beings, are subject to the effects of sin in the world. This means we are prone to actively sin with our bodies and minds. We also suffer the effects of other people’s sin in our bodies and minds. And our bodies and minds suffer the deleterious effects of death infecting every part of creation.

Applying the Bible’s framework of brokenness to clinical depression reveals some important insights about this illness.

Personal sin

You may have noticed that one of the nine symptoms for Major Depressive Disorder is feeling inappropriately guilty, which flows from a style of thinking that personalises bad things that happen. For a person with depression, this experience is incredibly difficult. It can feel impossible to get out from under the weight of guilt, and your attention is skewed to notice evidence that you are a burden to others and unworthy of love. Therefore, where depression is present, a person’s conscience is not a good guide for their perception of whether they are living rightly or sinning. In a situation where personal sin is somehow bound up in a person’s depression, rebuke of that sin is unlikely to help. Instead, it will increase guilt and disempower the person to change. It is far better in this moment to lean into promises that assure us of the overflowing nature of God’s grace, like this one:

the Spirit helps us in our weakness. We do not know what we ought to pray for, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us through wordless groans. And he who searches our hearts knows the mind of the Spirit, because the Spirit intercedes for God’s people in accordance with the will of God.

— Romans 8:26b,27

What a comfort to know that where our own thoughts and conscience are unsteady, and when we sin, we are still seen and understood by the Spirit, who groans on our behalf in the Godhead.

Other people’s sin

While it is an obvious statement that we are shaped by the individuals and communities around us, when it comes to mental illness, we often assume that the core problem lies within the sufferer. It is easy to be blind to the effects of other people on the development of a mental disorder like depression. There is a myriad of possible examples: the emotionally absent parent, the persistent character attacks of an online bully, the relentless demands of a workplace culture. Moreover, the systems of relationships we operate in—such as our immediate families—can set us up to experience mental health challenges. An example often cited is where a family can’t handle underlying anxiety in healthy ways, and so creates a need for one member to be the ‘patient’ so that everyone else can unite to help them or exclude them. If these comments resonate, counselling could be a great space to explore these things. Counselling from a family systems perspective will give particular focus to the effects of your relational systems.

The effects of death on creation

As a part of creation, our bodies—including our brains—groan as we wait for Jesus to renew all things. Depression is certainly an illness of psychology (thoughts and emotions), but it also has a very physical dimension in both cause and impact. Hormonal shifts during and after pregnancy, for example, can be significant enough to trigger depression. Certain physical illnesses that interact with the body’s chemistry, such as endocrine disorders, and those that impact the brain’s structure such as a tumour, can also be key factors in a diagnosis of depression. Further, research on how the brain regulates emotion shows that in most cases depression is a disorder of biochemistry, where mood-related neurotransmitters that carry signals around the brain are disrupted. The three key neurotransmitters connected to mood are serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine. We know that there are habits of life that help the brain produce and support the functioning of these neurotransmitters, such as

- getting enough sleep,

- regular exercise,

- eating well,

- getting absorbed in activities that are intrinsically enjoyable to you such as dancing, jigsaw puzzles, photography, etc.

And, we also know that the right medication or other brain-based treatments can make a difference for a person suffering from depression, as they correct abnormalities in the brain’s chemistry. All this said, discussing the bigger picture of your health (including mental health) with your GP or a psychiatrist will bring the physical dimension of your depression into focus.

This survey of why a Christian might be depressed hopefully gives you a sense of the sheer complexity of this mental disorder. Though the gospel itself is stunningly simple, we should avoid the temptation to simplify the state of things in this broken world and in our broken selves. Rather, we need a framework that allows brokenness to be more complex than our explanations, healing to be slower than our patience can bear, and an ultimate solution that is more glorious than we could possibly imagine. By acknowledging our limitations, we entrust ourselves to our all-knowing, powerful, loving God.

Psychological treatments

Psychological based treatments include various kinds of talk therapy. A popular example is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) which looks at the relationship between the things we think and the emotions we feel. CBT helps people examine their own thoughts, critique assumptions beneath them (for example, questioning an underlying belief that everything will always turn out for the worst), and gives strategies for thinking more rationally. This approach is popular because research has shown repeatedly that it produces reasonably quick results. The author of this article (Alison) can also testify to its helpfulness from her own experience. However, it does have its limitations.

As a therapy focused on cognitions (thoughts) it is biased against treating emotions as a source of valuable information about our identity. CBT doesn’t give a lens for exploring existential concerns related to death or eternity. It doesn’t give a lens for your family system and the role that plays in your thinking and behaviour. And it doesn’t give a lens for the stories you tell about your life and what they mean for who you are and where you’re going. But thankfully, there are other therapeutic approaches that do address these and other angles.*

If you do intend to see a therapist or psychologist, you may choose to find one who uses an approach that interests you. Alternatively, deciding on a therapeutic approach might be too intimidating, and that’s ok! The best piece of advice is to find someone you feel comfortable with, and this may mean trying a couple of therapists before you find the right one. A good rapport with the person providing counselling is a key factor in the potential success of therapy.

*Emotion Focused Therapy, Existential Therapy, Family Systems Therapy and Narrative Therapy, respectively. These are a sampling of a broad range of therapeutic approaches.

Physical treatments

A GP and especially a psychiatrist have the specific expertise required to decide when and what physical treatments are necessary. Physical treatments are stepped up in intensity depending on the severity of the depression, and whether other treatments (such as counselling) have made a difference. The main types of physical treatments include medications which interact with the brain’s chemistry to enable better functioning, and neurological stimulation such as electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). The Black Dog Institute offers a helpful summary of how these treatments work.

It may at first feel daunting to walk down the road of using physical treatments for a mental disorder. Asking questions of your doctor to set expectations for how long it may take to have an impact and possible side-effects, as well as what the treatment is doing in your brain, will help you feel comfortable with decisions. It might also help to note a little precedent in the words of the Apostle Paul to his ministry apprentice, Timothy:

Stop drinking only water, and use a little wine because of your stomach and your frequent illnesses.

— 1 Tim 5:23

This might seem like surprising advice to see in the Bible! It is a delightfully earthy acknowledgment of our embodied nature as creatures, and gives us permission to find help in the form of medicines and the like.

Self-help and alternative treatments

This category includes foods and supplements known to help with brain functioning, physical exercise, and practices like mindfulness and meditation. A brief word on two of these.

Exercise

Many benefits flow from integrating some kind of regular exercise in your life: improved sleep, increased energy levels, distraction from negative thoughts, social support if done with others, and the self-esteem boost that comes from doing a positive thing for yourself… to name a few. And you may be relieved to hear that exercise need not be vigorous to unlock these benefits. Set small goals and celebrate when you do them! Goals like: a walk around the block, choosing the stairs over the lift, doing some gardening. This article from the Mayo Clinic offers some relevant research and suggestions.

Mindfulness and meditation

“Mindfulness is the idea of learning how to be fully present and engaged in the moment, aware of your thoughts and feelings without distraction or judgment.” (Headspace)

Meditation is a practice that trains us to be more mindful. Meditation has a long heritage in Judeo-Christian tradition. Thousands of years before ‘mental health’ was even a category, songwriters gave us Psalms meditating on the character of God amid joy and lament and everything in-between.

Mindfulness meditation from Buddhist philosophy entered the field of psychology as a treatment option in the late 1970s, and since then has accrued extensive evidence of its positive impact for those experiencing mood disorders such as depression and anxiety. It is a treatment that is very easy to access from the comfort of your home through various apps and online resources (Headspace, quoted above, is a great example).

While many of these resources have stripped away the spiritual focus of their Eastern origins, some discernment is encouraged if you choose to make use of them. Through guided meditation, Headspace and similar apps will teach you valuable concepts about how your mind works and how negative emotions can get the better of us. Regular use will train your mind in the ability to press pause and reconnect with your body and the present moment. But, embedded in these meditations are ideas that sometimes feel at odds with a Biblical understanding of humanity, spirituality, and brokenness. So, a potentially worthwhile resource, but use discerningly.

Alternatively—or additionally—you may be interested in exploring Christian guided meditation resources. Abide and Soultime are two popular apps. Contemplative prayer is another practice that can cultivate mindfulness, though in this case, ‘health benefits’ come when we take our attention off ourselves and onto God’s presence. And, simply opening up the Psalms and using them to inform your prayers or just remind yourself that God gets it, is a practice that requires no subscription or push notification.

How can I learn more or get help?

Connect yourself to help immediately

Lifeline 13 11 14 (24-hour crisis support and suicide prevention services. Call, text or chat online to connect with someone trained to help.)

If life is in danger call 000

Beyond Blue Support Service (call, chat online or email with a mental health professional)

Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467

MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78

Websites with easy to digest information

and ways to find support

PANDA (Perinatal Anxiety & Depression Australia)

Youth focused resources

Online wellbeing and resilience program for 12–18-year-olds, a free service by the Black Dog Institute

headspace (National Youth Mental Health Foundation) providing early intervention and mental health services to 12–25-year-olds

Books by Christian authors

(in order from shortest to longest by page number)

Christians Get Depressed Too, David Murray, 2010

Down Not Out: Depression, anxiety and the difference Jesus makes, Chris Cipollone, 2018

Spurgeon’s Sorrows: Realistic hope for those who suffer from depression, Zack Eswine, 2014

When Darkness Seems My Closest Friend: Reflections on life and ministry with depression, Mark Meynell, 2018

When Life Goes Dark: Finding hope in the midst of depression, Richard Winter, 2012

Other helpful books

Mental: Everything you never knew you needed to know about mental health, Dr Steve Ellen & Catherine Deveny, 2018

Changing Minds: The go-to guide to mental health for you, family and friends, Dr Mark Cross & Dr Catherine Hanrahan, 2016

Alison Courtney holds a Master of Arts in Counselling from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Massachusetts, USA. She is also a secondary school teacher with pastoral care experience in Christian education. Presently, most of her time is spent raising two young children. When spare time occasionally presents itself, Alison enjoys making art.