Clinical Psychologist, Ruth Holt, spoke at the June 2024 Spotlight Session on ‘Living with the impact of childhood trauma’. This article summarises some key aspects of her presentation.

Read Living with the Impact of Childhood Trauma Part 2 for Ruth’s suggestions of how individuals and churches can respond well to these impacts.

Whatever our personal experience, trauma is an inherently troubling topic. As Ruth began her presentation, she read a beautiful verse of Scripture: ‘The Lord God is a sun and shield; the Lord bestows favour and honour’ (Psalm 84:11). She suggested we pray and ask for the warmth and protection of God’s love, and mentioned some other tools to help regulate strong emotional responses. In this article, we do not discuss the details of traumatic events, but in keeping with Ruth’s encouragement, please take care.

How childhood trauma differs from adult trauma

Diane Langberg, a psychologist and therapist who has spent over four decades working in the field of trauma, says, ‘Trauma is when suffering overwhelms human coping.’ Most adults will experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime (e.g., a natural disaster, a car accident, being abused, etc), but our ability to cope differs according to the resources available to us. And this is significant for children experiencing traumatic events—often they don’t have resources to draw upon.

Ruth highlighted three factors that distinguish childhood trauma from adult trauma. First, children lack certain things that adults usually possess:

- They may not have the language to understand or process what’s happening to them (lack of voice).

- They may not be aware that what is happening to them is wrong and therefore not have the ability to choose whether or not to engage (lack of choice).

- There may be no safe person to tell, or if they do speak up, that person doesn’t respond. This means that they may not have the capacity to get out of an abusive/distressing situation (lack of power).

Second, children are at a stage of development when they are unconsciously wrestling with big questions and forming templates of their world: What are people like? Who am I? Is the world safe? Their experiences shape their responses to these kinds of questions and become deeply embedded, not only in their thinking, but in their body, emotions and memory.

Third, all children are egocentric. They see themselves as the centre of the universe and hold themselves responsible for events occurring around them. For example, ‘I was a naughty kid, that’s why my parents divorced.’ These types of messages are often carried into adulthood.

Despite these common features of childhood, Ruth emphasised that the experience and impact of childhood trauma was unique for every person. It’s wise to avoid the formulaic approaches often found in social media and self-help books. In her clinical practice, Ruth wants to hear what is distinctive for the person sitting with her and seeks to offer the assistance that will be most helpful for each particular individual.

Our need for nurture

All human beings need regular experiences of love and nurture. God has wired us this way and we are impoverished without them. We are not designed to do life alone without the support of others who ‘have our back’.

Think of little babies. In their state of vulnerability, they depend upon others to look after them. Consistent and predictable care hardwires a sense of safety. They learn that when they cry, someone responds; that when they are hungry, they are fed. Ruth explained that the feeling of safety that develops in response to reliable caregiving provides what is known as co-regulation. And this is vital to learning the skill of self-regulation, i.e., being able to manage how we react to our feelings and experiences so that we can provide ourselves with a sense of safety. As children grow in a nurturing environment, they begin to internalise messages from their caregivers. Feeling loved by others communicates that you are lovable. When others view you with kindness and concern, you learn to see yourself through this lens. Over time, this enables a child to learn to self-soothe, even if in some circumstances they still need to run back to those stable and safe caregivers.

So, as we move through childhood, the way our caregivers see us and treat us is very significant in terms of how we come to look at ourselves. This is true for all of us, whether or not we’ve experienced childhood trauma. Whether we were viewed with eyes of compassion or eyes of judgment, we take on the messages that come our way.

When nurture is lacking

Sadly, in our less than perfect world, many experience a lack of safety with others, or their needs for love, connection, affirmation or stability have not been met. They may sense that they don’t really matter, or that love can be withdrawn or perhaps must be earned. Maybe they learned that touch comes in unsafe and scary ways.

Ongoing experiences of lack of safety and nurture impair our ability to regulate our feelings, impact our sense of self, and damage our connections with others. We might find it difficult to manage feelings of worry, anger, or frustration. Perhaps we experience states of hypervigilance or panic. Or we might shut down and ‘check out’ relationally.

As adults, we can become stuck in these types of states and use them as means to survive the demands of day-to-day life. Ruth listed a range of such strategies:

- Shutting down and not feeling anything

- Dissociating and having a fragmentary sense of self

- Seeking to appease and please others

- Being ‘responsible’; protecting and looking out for others

- Soothing oneself with other things, such as eating, alcohol, masturbation, or flights of imagination

- Trying to be the opposite of how the trauma felt, e.g., having felt powerless, present as being powerful

- Being hypervigilant

- Presenting to others as being ‘hopeless’

- Relying on oneself and sending the message you don’t need anything from anyone

These may assist our coping a little, but they tend to be fairly blunt instruments that can interfere with healthy relating. Ruth pointed out that in our churches, often these sorts of behaviours are viewed only through a moral lens. Sinful behaviour might be evident, but she believes it’s important to ask, ‘Why is this person acting this way? What might this behaviour be seeking to solve?’ This will enable a more compassionate and redemptive response to those impacted by childhood trauma.

Why the impact of trauma differs from person to person

Ruth explained that childhood trauma will impact people in different ways. There are factors that can have a protective effect, while other factors tend to worsen the impact.

Protective factors include:

- Having a stable attachment to a caregiver prior to the abuse

- When speaking up, the child is believed and the abuse stops

- Having the language to speak of what has happened and being supported in processing the abuse

- The abuser is not family or a ‘trusted’ person

- Certain types of temperament

- Socioeconomic advantage

- Possessing individual strengths

- Having at least one reliable adult in one’s life

Worsening factors include:

- Having impaired attachments prior to the abuse

- The child is not believed

- Not having language to speak of what has happened and failure to support the child to process the abuse

- Further experiences of abuse

- The abuser was seen as ‘trusted’ and there is ongoing contact

- Certain types of temperaments

- Socioeconomic disadvantage

- Individual difficulties

- Adopting unhelpful coping strategies such as drugs/alcohol/sex

Differing responses to trauma extend to the spiritual realm and the ability of people to relate to God as adults. When God or spirituality is used as part of the abuse, it gets in the way of people understanding the truth about what God is like and the gracious love he demonstrates in the gospel. On the other hand, if spiritual factors play no part in the abuse, God might be viewed as a safe person and the church as a place of refuge and safety.

We develop schemas in response to unmet needs

Earlier we mentioned that the way we are treated by caregivers and others shapes how we view ourselves. When our needs are not met, it forms our self-understanding and behaviour in particular ways that become entrenched and influence our functioning as adults. These patterns are known as ‘schemas.’ When we feel as if our ‘buttons are being pressed,’ then a schema is likely in play.

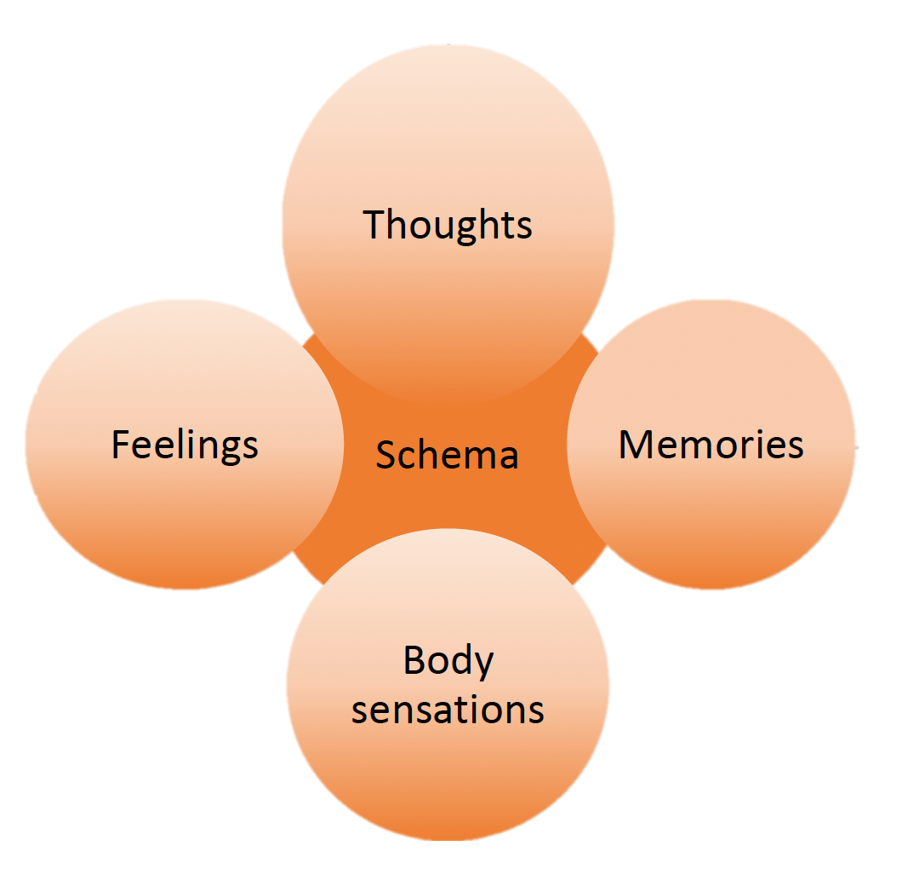

Schemas affect many areas of our functioning. Look at this diagram:

A schema involves a certain way of thinking about ourselves, a particular range of feelings and memories, and finding that our bodies respond in certain ways.

So, schemas are pervasive. They also often lie beneath our conscious awareness. For example, a person might say that they don’t trust anyone, but not know what has given rise to that attitude. Moreover, schemas tend to be self-maintaining. They are well-worn paths that continue to influence us over the long haul.

A common schema for those who’ve experienced childhood trauma is the Mistrust/Abuse schema. The person expects that others will hurt, abuse, humiliate, cheat, lie, manipulate or take advantage of them. Childhood trauma also often gives rise to:

- Abandonment/Instability schema: ‘I’ll be alone; people are not going to be there for me’; feeling anxious and sad

- Emotional deprivation schema: ‘I’ll never be understood or loved in the way I need’; feeling unseen and empty

- Defectiveness/Shame schema: ‘I’m inferior/broken/a fraud’; feeling shamed and sad

How schemas impact our relationship with God and how we function at church

The schemas we carry impact our relationship with God. Those with a Mistrust/Abuse schema tend to see God as unsafe—he will control me and not protect me. When the Abandonment/Instability schema is in play, God is unreliable—if I don’t keep him happy, he will leave me and stop loving me. The God of the Emotional deprivation schema is distant and demanding—I might ‘know’ that he loves me, but I can’t feel his love. For those with a Defectiveness/Shame schema, the sense is that God can never accept me—he reminds of my inadequacy, and I feel rejected by him.

The way schemas play out in church life can be quite paradoxical. The Mistrust/Abuse schema can result in trusting others too quickly and then finding they are let down. Or the opposite might occur—not sharing anything because it’s not safe. The Abandonment/Instability schema might mean staying on the fringes and not connecting. But again, perhaps the person will opt for the contrary behaviour of getting involved in everything. When the Emotional deprivation schema is in play, I might either overshare to receive whatever support I can when I can, or hold back and keep everything to myself. Finally, the Defectiveness/Shame schema might lead to sitting in a pool of guilt or putting in lots of effort to gain the approval of others.

Unfortunately, these schemas can become self-reinforcing in a way that doesn’t serve us well. For example, if a Defectiveness/Shame schema leads me to regularly ‘big note’ myself to try to have others think well of me, that behaviour might in fact achieve the opposite which reinforces my feelings of being defective.

It is clear, therefore, that the impact of childhood trauma is not limited to the period around the time of the abuse, but lingers on into adulthood in ways that have a significant impact on day-to-day functioning and relating.

Part 2 of Living with the Impact of Childhood Trauma summarises Ruth’s suggestions on how individuals and churches can respond in helpful ways.